Lesallan | April 22, 2025

Defining the Perfect (or Necessary) Being

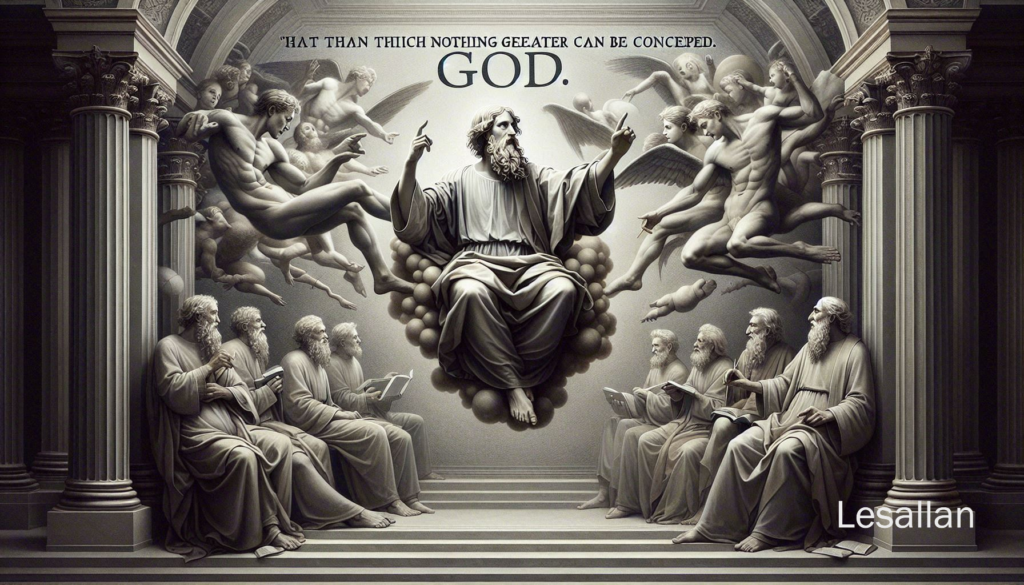

When philosophers speak of a Perfect Being, they talk about an entity whose nature encompasses every possible excellence or perfection. In Anselm’s framework (Anselm, N.D.), God is defined as “that than which nothing greater can be conceived.” This is not just a claim about moral or aesthetic superiority; it is a claim that existence itself is a marker of perfection. In other words, for a being to be perfect, it must exist, not merely as an idea in the mind but also in reality. If the greatest conceivable being were to exist only in thought, then one could imagine something even greater—namely, a being that exists in both the mind and reality—which would contradict its definition as the ultimate or maximal being.

Aquinas, on the other hand, takes a slightly different route. His approach often comes through the lens of contingency in the world. He argues that while many things in nature exist only by virtue of some external cause, there must be an uncaused, self-existent being those accounts for the existence of everything else. For Aquinas, this necessary being is the ultimate source and sustainer of all that exists, marked by perfection in its ability to cause, order, and sustain the universe. Despite methodological differences, both thinkers converge on the idea that a being possessing such maximal attributes must exist by necessity rather than mere possibility.

The Logical Structure of the Arguments

Anselm’s Ontological Argument

Anselm’s argument is primarily conceptual. It starts with the very definition of God as the greatest conceivable being. Here is how it unfolds:

Definition as the Starting Point:

If we define God as that which nothing greater can be conceived, then a being existing only in the mind would be less great than one that exists.

Existence as Perfection: Since existence is perfection (an attribute that makes a being greater), a being that is truly perfect must exist.

Logical Necessity: If we were to deny God’s existence, we would be caught in a contradiction—we would be saying that the greatest conceivable being lacks a perfection (existence), which is impossible.

This argument does not rely on empirical observation but rather on the internal logic of the concept of maximal greatness. If the idea of perfection inherently demands existence, then the very concept of God compels us to conclude that such a being must exist.

Aquinas’s Argument from Contingency

Aquinas’s approach to the problem from the angle of existential dependency in the universe:

Chain of Contingency: Everything we observe is contingent—each thing exists because something else brought it about or maintains it.

Need for a Necessary Foundation: If every entity were contingent, we’d face an infinite regress of causes. To stop this regress, there must be something that exists necessarily, a being whose existence is not dependent on any prior cause.

Ultimate Source of Perfection: This necessary being must be perfect, not contingent, and the uncaused cause. Its perfection is reflected in its ability to provide the foundation for all other things.

In both lines of reasoning, the arguments hinge on the move from conceptual definitions or causal chains to the conclusion that there must be a being with comprehensive perfection and necessity. Even when modal logic and “possible worlds” semantics are brought into the discussion—suggesting that if the existence of a maximally great (or perfect) being is even possible, then it must exist in every conceivable world—the conclusion is similar: ultimate perfection cannot be confined to the realm of ideas; it must be instantiated in reality.

Reflecting on the Implications

What emerges from these discussions is a picture of God as the ultimate grounding for all existence—a being who is not only the sum of all perfections but whose very nature is to exist necessarily, not by chance but by the very definition of greatness. The importance of such an argument in a broader metaphysical context is that it ties our understanding of human nature, contingency in the world, and ultimate purpose to the existence of something that is, in every respect, the source of all goodness and order.

As I reflect on this debate, it isn’t merely an intellectual exercise. It is an invitation to examine the assumptions underpinning our worldviews: If our best concepts of perfection demand existence, it pushes us to consider whether our intuitive sense of meaning and order might point toward a reality that is beyond randomness and mere accident.

In reading Nash (1999) and engaging with these classic arguments, one is not only challenged to think logically and critically but is also drawn into a deeper reflection on the nature of existence—a kind of metaphysical inquiry that asks us to consider the possibility that perfection, in its most maximal sense, isn’t just an idea but the foundation of all reality.

I would be curious to continue exploring these ideas further. For instance, how might modern modal logic refine or challenge these classical arguments? Or, how can we integrate personal, experiential aspects of faith with these strictly rational arguments? These questions open additional avenues for reflection that are as engaging as they are profound.

Blessings,

Lesallan

References:

Nash, R. H. (1999). Life’s ultimate questions. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan.

Anselm of Canterbury. (n.d.). Proslogion.

Aquinas, T. (c. 1265–1274). Summa Theologica.