Written By Lesallan

Ohio Christian University

BIB3510 Gospels: Luke (ONLF23)

Professor Daniel Rickett

September 7, 2023

The Synoptic Problem and the Triple Tradition

The Synoptic Gospels, consisting of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, share many narratives that are often presented in a similar order and with similar phrasing. In contrast to these synoptic texts, John’s Gospel is distinct. The term “synoptic” derives from the Greek word σύνοψις, meaning “a seeing all together, synopsis” (Harper, n.d.). This substantial content, structure, and language similarity is commonly attributed to literary interdependence. For centuries, scholars have debated the synoptic problem, seeking to understand the precise nature of the Gospels’ literary relationship. This problem is considered “the most fascinating literary enigma of all time” (Goodacre & Duke University Libraries, 2001), though no definitive answer has been found. The prevailing view is that Mark was the primary source used by both Matthew and Luke, and that they also drew from a hypothetical document known as Q (Goodacre & Duke University Libraries, 2001).

The triple tradition is a testament to the power and influence of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. These sacred texts offer readers different words and phrases in English, but their shared stories and teachings about Jesus unite us all. The triple tradition includes many powerful accounts, such as John the Baptist’s ministry, the Baptism and temptation of Jesus, and the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law. These stories remind us of the transformative power of faith and inspire us to live a life of compassion, kindness, and love. The triple tradition’s passages are arranged in the same order in all three gospels, highlighting the unity and consistency of these powerful messages.

In the field of Biblical scholarship, the term “triple tradition” is commonly used to describe the universal material found in the Synoptic Gospels – Matthew, Mark, and Luke. While researching, this student was unable to uncover the originator of this term. The term has been in use among scholars for a considerable length of time to describe the shared stories, teachings, and sayings of Jesus found in all three Gospels. There are many examples of the triple tradition found in the Holy Christian Bible, such as “The Baptism of Jesus” by John the Baptist (Matthew 3:13-17, Mark 1:9-11, Luke 3:21-22, ESV), “The Temptation of Jesus” in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-13, ESV), and “The Last Supper” (Matthew 26.17–30, Mark 14.12–26, Luke 22.7–38, ESV), among others.

The most important example of the “triple tradition” is the “Arrest, Trial, and Crucifixion” (Matthew 26:47-27:56; Mark 14:43-15:47; Luke 22:47-23:56, ESV) of our Lord and Savior Jesus. Finally, and most importantly, the final thing not part of the triple tradition is the “Resurrection of Jesus.” The Resurrection made believers out of many in the days that Jesus walked this earth. There are many examples found in the four Gospels, in the Book called the Bible, such as “The Arrest and Trial Before Sanhedrin” (Matthew 26:47–27:2; Mark 14:43–15:1; Luke 22:47–23:1, ESV). “The Trial before Pilate” (Matthew 27:2–26; Mark 15:2–15; Luke 23:2–25, ESV). “The Crucifixion” (Matthew 27:27–56; Mark 15:16–41; Luke 23:26–49, ESV). This triple tradition concludes with “The Resurrection” found in Matthew 28, Mark 16, and Luke 24 (ESV). In the books of Matthew 28 (ESV), Mark 16 (ESV), and Luke 24 (ESV), we find the Great Commission being conveyed by Jesus to His disciples. This commandment instructs them to spread the word of God to all nations, welcoming them into the faith through baptism in the name of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. Additionally, Jesus urges His followers to teach and guide the new believers in obedience to His teachings. He assures them of His constant presence with them until the end of time.

The triple tradition accounts for about 76% of Mark’s, 41% of Matthew’s, and 46% of Luke’s (Alderman, 2009). It shows that the three gospels have a common source or literary dependence, widely attributed to Mark being the earliest Gospel and a source for Matthew and Luke.

Some other observations I have about the similarities and differences between the synoptic gospels are the Gospel of Mark (ESV), which is the shortest and the most concise Gospel, while Matthew and Luke are longer and more detailed. Mark often uses the word “immediately” to show the urgency and intensity of Jesus’ ministry. Matthew and Luke share some material that is not found in Mark, such as the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7, ESV) or the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:20-26, ESV), the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:5-15, Luke 11:1-4, ESV) and some parables. This material, the double tradition or Q source, is believed to be derived from a hypothetical document containing Jesus’ sayings (Alderman, 2009).

The Gospel of Matthew (ESV) highlights Jesus’ fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies and his significance as the Messiah, the long-awaited king of Israel. At the outset of his Gospel, Matthew presents a genealogy that traces Jesus’ lineage back to Abraham and David. Additionally, Matthew incorporates multiple allusions to Moses and the Law, including the five discourses that parallel the five books of the Torah.

The Gospel of Mark depicts Jesus as the Son of God, who has come to earth with a message of great importance. According to Mark, the kingdom of God is near, and all should turn away from their previous ways and embrace the Gospel. Mark establishes early on that Jesus is indeed the Son of God, evident when John the Baptist baptized him. Mark’s account of Jesus’ ministry is concise and straightforward, focusing more on his actions than his words. He moves swiftly from one event to another, frequently using the adverb “immediately.” The primary goal of Mark’s Gospel is to present and defend Jesus’ universal call to discipleship. He frequently revisits this topic, dividing his audience into those who follow Jesus and those who oppose him. Mark achieves this goal by describing Jesus’ character and teachings.

In his Book, Luke portrayed Jesus as the savior of all people, especially the poor, oppressed, marginalized, and outcasts. Luke begins his Gospel with a prologue that addresses Theophilus, a Gentile reader, and shows how Jesus’ birth and ministry are connected to God’s plan of salvation for all nations. Luke also emphasizes the role of women, the Holy Spirit, and joy in Jesus’ story.

The explanation of “literary dependence” (Bauer & Traina, 2014) suggests that the synoptic gospel writers used one or more of the other gospels as sources for their accounts. Most scholars agree that Mark was the first Gospel written, and that Matthew and Luke used Mark as a basis for their narratives, adding or omitting details according to their purposes and audiences. Some scholars have also proposed that Matthew and Luke used another common source, called Q (Alderman, 2009), that contained sayings of Jesus not found in Mark. This theory can account for the significant material overlap among the synoptic gospels and variations in wording, order, and emphasis.

“Oral tradition” (Bauer & Traina, 2014) suggests that the synoptic gospel writers relied on the oral transmission of stories and teachings of Jesus that circulated among the early Christian communities. These oral traditions were shaped by the memory, interpretation, and needs of the believers who preserved and passed them on. The gospel writers then selected, arranged, and edited these traditions according to their own theological perspectives and intended audiences. This theory can account for the synoptic gospels’ similarities in content and structure and the differences in style, detail, and perspective.

Divine inspiration implies that the Holy Spirit guided the synoptic gospel writers to write their accounts of Jesus’ life and ministry. The Holy Spirit ensured that they recorded the essential facts and truths about Jesus while also allowing them to express their own personalities, insights, and emphases. The gospel writers also wrote for different audiences and situations, addressing different questions and concerns about Jesus and his message. This theory can account for the unity and diversity among the synoptic gospels and their reliability and authority as God’s word.

The different explanations have different strengths and weaknesses, and different scholars have different opinions and arguments. I can only share some factors that may support or challenge each explanation.

Based on the verbal agreement, common order, and editorial changes found in the synoptic gospels, it appears likely that the later writers borrowed and adapted from the earlier ones. This theory offers a straightforward explanation for the similarities and differences between the gospels. However, this idea has potential challenges, such as why Matthew and Luke diverged from Mark’s account in certain places or did not incorporate each other’s material. Additionally, the existence and content of Q (Alderman, 2009), a hypothetical document, has yet to be confirmed.

The tradition of sharing stories orally was prevalent in the first-century Mediterranean world, and it played a significant role in preserving history and cultural norms. This practice was instrumental in shaping the early Christian communities and passing down the teachings of Jesus. The gospel writers exhibited creativity and flexibility in selecting and organizing their material, allowing for diverse interpretations. Despite these strengths, this explanation faces challenges, including accounting for the remarkable degree of agreement among the synoptic gospels, particularly in wording and order. Additionally, the reliability and accuracy of oral transmission can be influenced by various factors, such as memory, interpretation, distortion, and adaptation.

Divine inspiration is supported by the faith and testimony of the Christian tradition, which affirms that God inspires the synoptic gospels and is authoritative for the church. It also respects the diversity and individuality of the gospel writers, whom the Holy Spirit guided to write their accounts according to their own purposes and audiences. However, this explanation also faces challenges, such as how divine inspiration can account for the human aspects of the synoptic gospels, such as literary dependence, oral tradition, historical context, theological perspective, stylistic variation, and textual criticism. It also depends on one’s understanding and definition of inspiration, which may vary among denominations and traditions.

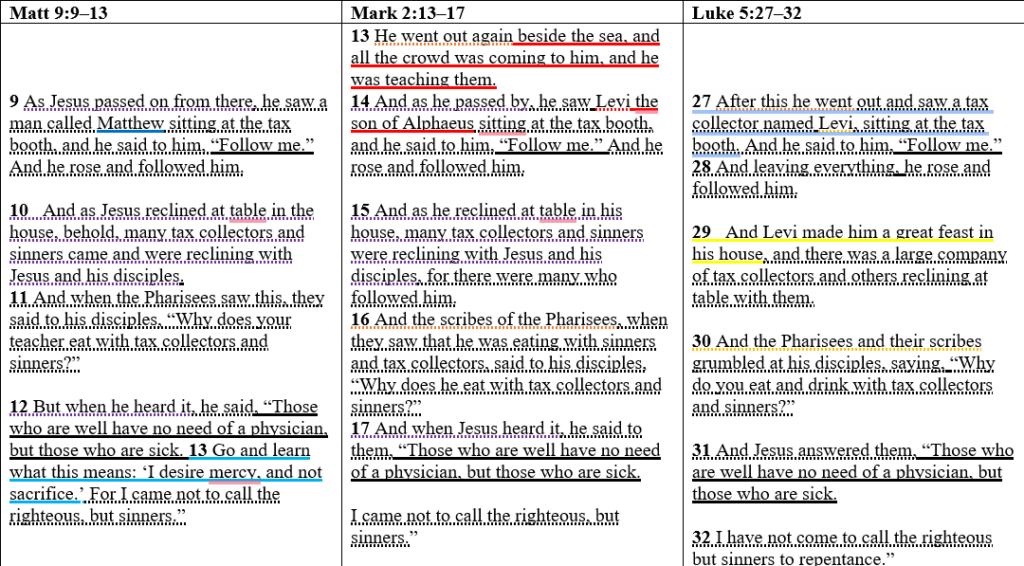

Despite their similarities, the Gospels contain several differences on various levels. Even in almost identical passages, there are slight variations in word order, vocabulary, syntax, style, and grammar. Additionally, there are discrepancies in other details, as evidenced above. For instance, sometimes names are included or omitted or are presented differently, such as Matthew being referred to as Levi in Mark 2:14 (ESV) and Luke 5:29 (ESV). Moreover, some accounts include extra information, such as the Hosea quote added in Matthew’s version below (Matthew 9:13, ESV). On occasion, it is observed that distinct, yet interchangeable Greek words are employed in parallel passages. Although these variations do not significantly modify the narrative, they are substantial enough to warrant consideration. This indicates the importance of meticulous attention to detail when analyzing and interpreting Greek texts.

References:

Alderman, I. M. (2009). The Synoptic Question. https://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/TB3_SynopticQuestion_IA.pdf

Bauer, D. R., & Traina, R. A. (2014). Inductive bible study – a comprehensive guide to the practice of hermeneutics. Baker Publishing Group.

Bratcher, D. (2018). The Synoptic Problem: The Literary Relationship of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Www.crivoice.org. http://www.crivoice.org/synoptic.html

Goodacre, M., & Duke University Libraries. (2001). The synoptic problem: a way through the maze. In Internet Archive. London, New York: T & T Clark International. https://archive.org/details/synopticproblemw00good

Harper, D. (n.d.). Synoptic | Etymology, origin and meaning of synoptic by etymonline. Www.etymonline.com. https://www.etymonline.com/word/synoptic